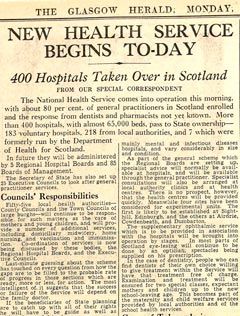

Delivery day – July 5 1948

Press coverage on the day welcomed the new arrival. The mood was celebratory but not over the top. Staff had their usual job to do – treating patients.

The real impact was in areas where there was limited or no public provision like dental surgeries, GP practices and opticians.

For the first time everyone in Scotland now had access to proper medicine on prescription. Those plagued with rotten teeth were able to see a dentist for the first time. Previously-deaf people could hear with new aids.

The new NHS had to be seen to be believed. Half a million Scots (one tenth of the entire population) were able to have free spectacles within four months of its inception. Half a million also got free dentures in the first year.

A healthy start

The first year of the NHS provided the biggest single improvement in the everyday health and well being of the people of Scotland – before or since.

Demand was overwhelming but it was met. Bevan’s achievement was all the more astonishing in such an era of austerity.

Arthur Woodburn was pleased to report to the Cabinet that the Scottish birth had been remarkably smooth.

Nearly all doctors, dentists and opticians were taking part. There were 425 hospitals with 60,000 beds.

Scotland had provided prototypes for the NHS. The UK structure brought advantages in return. Services were available across Britain. National Health Service staff had common salary scales which gave a relative advantage to Scottish health workers whose wages were generally lower than elsewhere.

Doctors no longer had to send out monthly bills. Many had substantial pay increases and all had secure salaries for the first time.

Early teething

Within a month of patients coming into the new Scottish NHS, one of the world’s greatest novels was heading in the other direction.

George Orwell left Hairmyres Hospital in Lanarkshire after lengthy treatment for tuberculosis (TB) during which he fleshed out the second draft of 1984. Big Brother was born the following year.

The infant NHS faced an immediate crisis. Scotland was already the sick man of Europe – the only country apart from Portugal – facing an alarming rise in TB rates.

The outlook for patients was certainly brighter thanks to new huge advances in drug and other treatments. But these were costly – $320,000 for the 50 kg of American streptomycin which the British Medical Research Council was testing.

- Further information

- Orwell

Audio clip:

Professor Jimmy Williamson George Orwell as a patient

“There was a colossal amount of unmet need that just poured in. There were women with prolapsed uteruses literally wobbling down below their legs. It was the same with hernias. You would have men walking around with trusses holding these colossal hernias in. They were like that because they couldn’t afford to have it done.”

Dr John Marks, who graduated as a doctor on July 5, 1948

“We had seen the grim poverty in which people lived and the fact that they had no access to a doctor unless they could pay – and they couldn’t pay.

“It was that sense of optimism and the consensus view that the NHS was a ‘damn good thing’ that allowed the NHS in Scotland to overcome the difficulties of inadequate resources, an antiquated infrastructure and the overwhelming demands of an enthusiastic public.”

Dr Mark Fraser, then a young Edinburgh doctor